Basic Understanding of Variables

Understanding variables is a fundamental computer programming skill.

Dependencies

This skill has no dependencies.

Goal

When you teach this skill, your goal is to make it so that students know that a variable is a container for information*.

*For most intents and purposes, it’s fine to define a variable as a container for information. However, that definition is not 100% accurate, and students may not be able to fix certain bugs if they only know that definition. For a more accurate definition of variables, see this section of the Python documentation.

Activities

Here are some activities that you can do in order to teach this skill.

Deconstructing a video game

-

Ask students to choose a classic arcade game. Technically, you can do this activity with any kind of game, but it’s easier to do with classic arcade-style games.

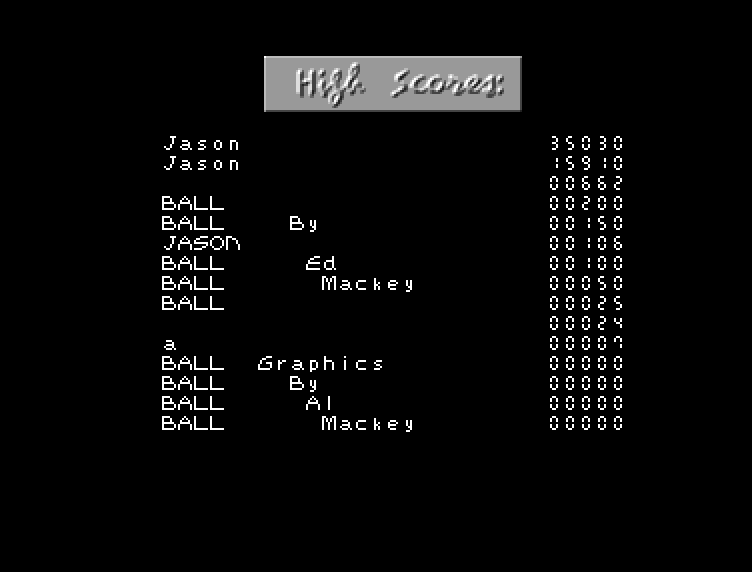

Throughout the rest of this guide, I’m going to use the game Ball as an example:

-

Ask students if there’s anything that changes while you play that game.

Here’s some examples of things that change while you’re playing Ball:

- Player 1’s score

- Player 1’s number of lives

- The length of the paddle

- Whether it’s player 1’s turn or player 2’s turn

- Which level you’re currently on

-

Take one of the examples that students gave you, and draw a box for it on the board:

-

Explain that variables are containers for information. The box that you drew on the board is like a container, so we’ll use it to represent the variable that we’re creating.

-

Ask students to come up with a name for the variable.

You may have to help students come up with a good name for the variable. Let’s say that we’re creating a variable for Player 1’s score. Here are some good names for that variable:

- score

- player_1_score

- p1_score

- number_of_points

Here are some bad names for that variable:

- number

- x

-

Once you’ve come up with a name for the variable, write that name the box:

-

Ask students what will be stored in the variable when the game starts. Write their answer inside of the box.

In Ball, player 1’s score starts at 0:

-

Come up with a situation that would cause the variable to change, and then ask students what would happen in that situation.

In my example, I would ask students “when player 1 breaks a brick, what’s going to happen to the

p1_scorevariable?” -

Once students answer, erase what you had written in the box and replace it with their answer.

In my example, a student might say that breaking a brick would make player 1’s score go up by 7:

-

Repeat step 9 a few times, but ask different students what would happen to the variable. This helps you verify that everyone understands what you’re explaining.

-

Repeat steps 2–10 once or twice with different variables. If you started by using player 1’s score as an example, then move on to using player 1’s lives or the current level number as an example.

Make sure that at least one of your examples is a string. It’s easy to accidentally only do examples that are numbers. I often use the game’s high score screen in order to come up with examples of string variables: